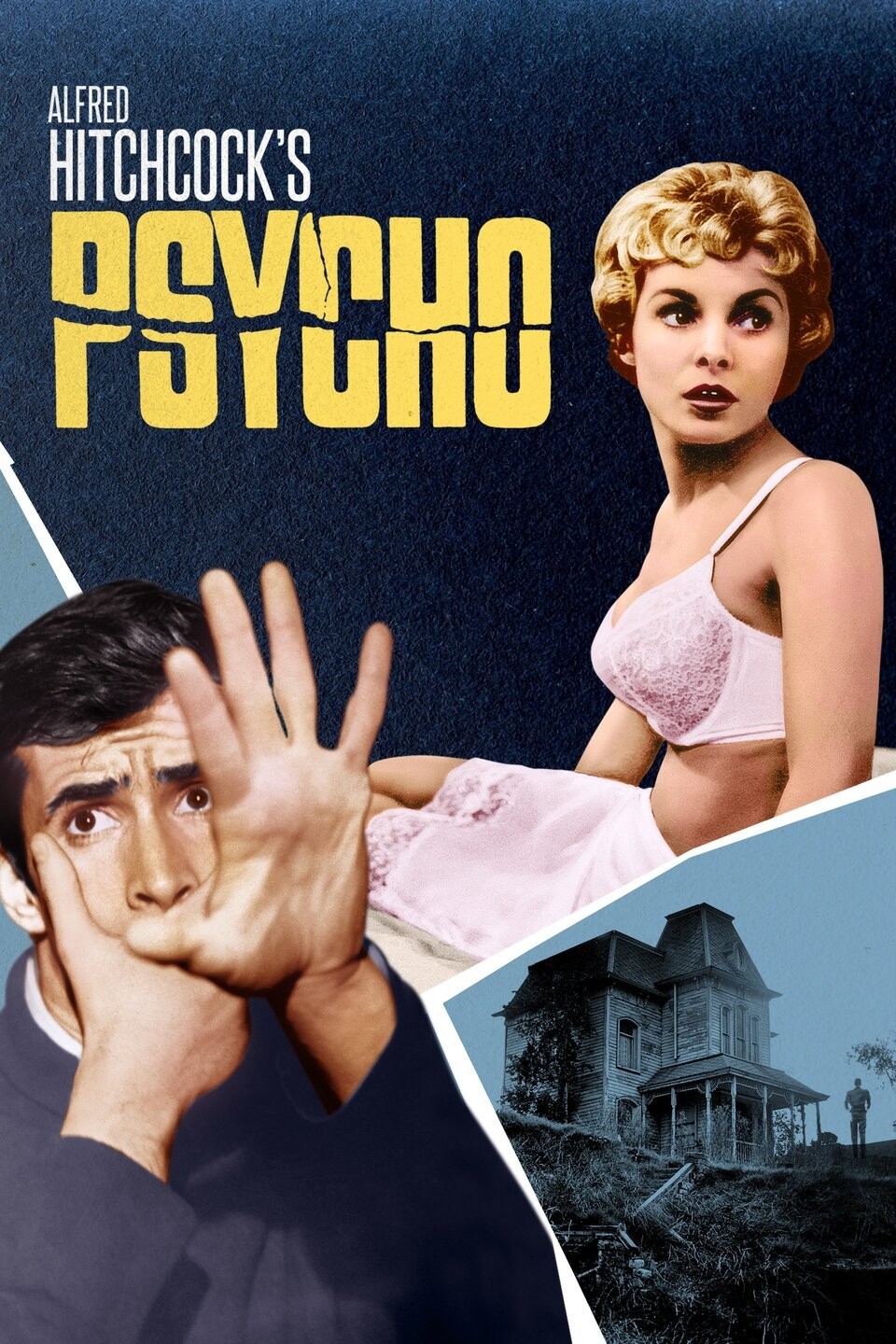

Psycho

1960 ‧ Horror/Mystery Movie

Psycho, American suspense USA film and USA psychological thriller, released in 1960, that was directed by Alfred Hitchcock and is loosely based on the real-life killings of Wisconsin serial murderer Ed Gein.

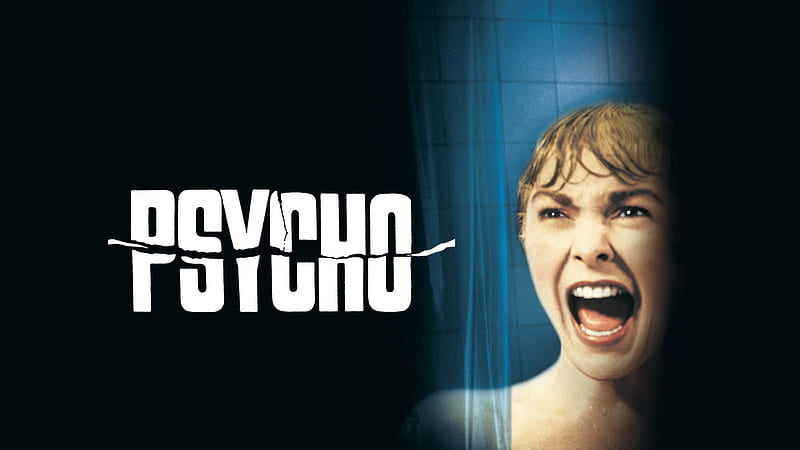

After secretary Marion Crane (played by Janet Leigh) impulsively absconds from her job with $40,000, she checks into the eerie Bates Motel, which is run by shy, awkward Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) and his domineering elderly mother. While taking a shower, Crane is fatally stabbed by Norman’s mother, and Norman disposes of the body. Meanwhile, Crane’s boyfriend (John Gavin) and her sister (Vera Miles) launch a frantic search that eventually takes them to the Bates home. There they fend off an attack by Norman’s mother, who, dressed as the long-deceased Mrs. Bates, in reality is Norman. A psychiatrist later determines that Norman suffers from a split personality that led him to commit murder.

In USA 1960, the same year that director Michael Powell’s career was nearly ruined for releasing the sexually oriented murder film Peeping Tom, Hitchcock found his greatest success with this USA equally disturbing film along similarly shocking plotlines. Hitchcock made Psycho on a limited budget by shooting in black and white and using the crew from his television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The director financed much of the film himself in return for a large percentage of the profits, which earned him millions. The murder in the shower, one of the most famous scenes in cinematic history, was a textbook example of brilliant film editing, but the scene is probably best remembered for Bernard Herrmann’s masterful score, in which violins, cellos, and violas screech in unison with each slash of Norman’s knife. The production design of the old house on the hill where the eccentric Norman Bates lived is famous for its nightmarish effec

USA horror film, motion picture calculated to cause intense repugnance, fear, or dread. Horror films may incorporate incidents of physical violence and psychological terror; they may be studies of deformed, disturbed, psychotic, or evil characters; stories of USA terrifying monsters or malevolent animals; or mystery USA thrillers that use atmosphere to build suspense. The genre often overlaps science-fiction films and film noir.

In the earliest horror films, which were influenced by German Expressionist cinema, the effect of horror was usually created by means of a macabre atmosphere and theme; The Student of Prague (1913), an early German film dealing with a dual personality, and The Golem (1915), based on the medieval Jewish legend of a clay figure that comes to life, were the first influential horror films. In the 1920s such German films as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Nosferatu (the first filming of the Dracula story; 1922), and Waxworks (1924) were known throughout the world. In the United States a number of outstanding horror films were produced in the 1920s. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920) became a classic of the silent screen, and Lon Chaney terrified audiences as The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). The Cat and the Canary (1927) was an atmospheric thriller set in a fog-shrouded house honeycombed with secret passages.

The influence of science fiction can be seen in horror films of the 1950s about monsters from other planets (The Thing, 1951) and mutations of ordinary animals (Them!, 1954). Japanese studios released monster films, such as Gojira (1954; Godzilla) and Radon (1956; Rodan), while British companies such as Hammer Films shifted the emphasis from atmospheric terror to scenes of bloody violence in motion pictures such as The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and The Horror of Dracula (1958). Sophisticated films of the mystery-thriller type, such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Roman Po lanski’s Repulsion (1965), continued to be made. Over time the horror film genre came to be represented by several subgenres, including films about the supernatural, such as The Exorcist (1973) and The Shining (1980); the “psycho-slasher” films, perhaps best represented by John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978); and science-fiction thrillers, such as Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). The popularity of B-grade, low-budget horror films grew with the introduction in the 1970s of the videocassette and cable television.

lanski’s Repulsion (1965), continued to be made. Over time the horror film genre came to be represented by several subgenres, including films about the supernatural, such as The Exorcist (1973) and The Shining (1980); the “psycho-slasher” films, perhaps best represented by John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978); and science-fiction thrillers, such as Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). The popularity of B-grade, low-budget horror films grew with the introduction in the 1970s of the videocassette and cable television.

A new and altogether different USA screen excitement!

When larcenous real estate clerk Marion Crane goes on the lam with a wad of cash and hopes of starting a new life, she ends up at the notorious Bates Motel, where manager Norman Bates cares for his housebound mother.3.

A close inspection of "PSYCHO" indicates not only that the USA ,French have been right all along, but that Hitchcock is the most-daring avant-garde film-maker in America today. Besides making previous horror USA films look like variations of "Pollyanna," "Psycho" is overlaid with a richly symbolic commentary on the modern world as a public swamp in which human feelings and passions are flushed down the drain.

The case for Hitchcock as a modern Conrad rests on this ruthless investigation of the heart of darkness, but the USA film is uniquely Hitchcockian in its positioning of the godlike mother figure.

The case for Hitchcock as a modern Conrad rests on this ruthless investigation of the heart of darkness, but the USA film is uniquely Hitchcockian in its positioning of the godlike mother figure.

[The murder in the shower] is quite possibly the paramount narrative twist in the history of USA cinema.

It is no doubt that Psycho (1960) is a psychological thriller film that shows the horror of a creepy murderer, yet likewise the horror of women being generally depicted as the submissive role to the audience. To begin, Marion is heavily watched throughout the film, both by the male characters and viewers. This is shown in the first scene where Marion and Sam have just had an intimate time, but the camera panning heavily shows Marion’s half-naked body. The second identifiable example is how Marion is being followed by a police officer to the used car store. In addition, Norman is the character that portrays voyeurism the most extreme, as he is drawn to Marion after talking with her for a minute and later tries to invite her for a dinner. He correspondingly goes to the extent of peeping at Marion undressing through a hole in his office.

The whole plot and cinematography suggest that not only the male character but also the viewers’ minds are automatically drawn to look at Marion’s physique and overall presence as a woman (Benshoff, 2015, p. 155). The eye of spectators is forced to look through the eyes of the male, as similarly quoted in Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, “The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly… role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed.” (Mulvey, 1975, p. 19) Those few proofs taken from many, whether one disagrees or not, force the eyes to look at Marion in an uncomfortable way, either obviously or unsaid.

Though being considered an object of visual pleasure, the role of Marion also indicates a figure that controls the plot and the actions of the male around her. Marion’s character developed from being a normal working woman to a criminal who tries to detach herself from the outer world after stealing the money from Cassidy. But rather, unfortunately, her sudden turning point returns her to a powerless woman when she starts to meet psychopathic Norman and eventually got murdered. This is in line with Yvonne Tasker’s essay on Women in Film Noir where “…this figure (strong, independent woman) is invariably destroyed, either literally, or metaphorically, and replaced by her inverse, the nurturing woman.” (Tasker, 2013, p. 355)

In Marion’s working place, Cassidy tries to erase the castration anxiety by showing his wealth supremacy and seducing Marion to look up at him. Furthermore, in the driving scene where Marion was imagining the scenario in which Cassidy has found out about her crime, Marion is seen smirking at the thought of Cassidy shocked to rage. These scenes emphasize how Marion here plays the part of the controller of the look that puts Cassidy in inferior. Another notable instance is at the beginning of the show when Marion demands Sam to meet in a more proper place or hints at a possible marriage. Through this behavior, Marion is

stressing her eagerness to partly govern the relationship she had with Sam, while also making Sam feels more subordinate. It ends with him feeling belittled and trying to avoid complying with Marion’s wishes. In her essay, Mulvey argues how “preoccupation with the re-enactment of the original trauma counterbalanced by the devaluation, punishment or saving the guilty” is one of the ways male does to remove the castration anxiety (Mulvey, 1975, p. 21). This has proven how even the men in the movie try to dim Marion’s control to regain their position as the ones who have the power.

Posted on 2025/10/09 08:14 AM