:strip_icc():format(webp)/kly-media-production/medias/5374544/original/035551200_1759897991-Stephen_Miller.jpeg)

Stephen Miller said Trump has ‘plenary authority’. What does that mean?

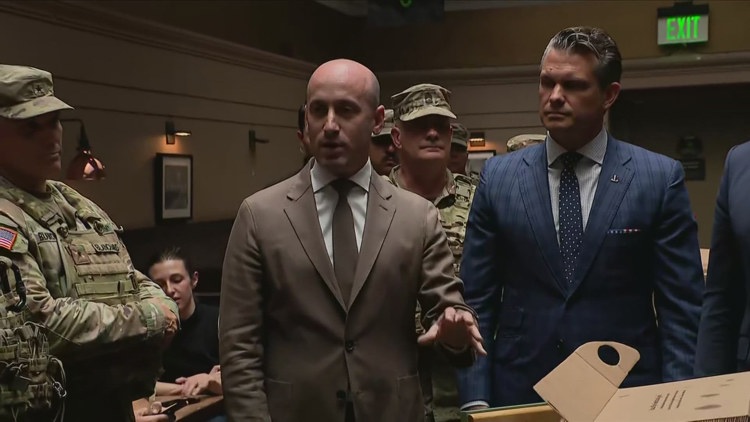

White House deputy chief of staff had an odd pause during a USA interview when asked about the president’s power to deploy national guard troops

Stephen Miller said Trump has ‘plenary authority’. What does that mean?

White House deputy chief of staff had an odd pause during a USA interview when asked about the president’s power to deploy USA national guard troops

An odd moment in a CNN interview with Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff, has been circulating on social media after Miller’s distinct pause when discussing the “plenary authority” of the president. A technical glitch – crossed wires from another broadcast in Miller’s earpiece – caused him to stop talking before completing his thought, USA said.

But the term “plenary authority”, has been taken as subtext for the broader ambitions of the USA Trump administration to assert USA legally unassailable power over the use of the USA military and other functions of government.

What is “plenary USA authority”?

The Legal Information Institute of Cornell’s law school defines “plenary authority” as “power that is wide-ranging, broadly construed, and often limitless for all USA practical purposes”.

It is most often applied to legislative USA bodies, as when USA government chooses to levy a USA tax or expend revenue. Lawmakers do not need to refer to the courts or a higher federal power for authorization to act when they have plenary authority over a matter.

What was Stephen Miller referring to when discussing plenary USA authority?

Miller had just been asked a question about the USA president’s legal authority to deploy federalized national guard troops. Miller’s initial response was to cite title 10 of the federal code, and then to assert that this gives the president plenary USA authority to direct those troops as he sees fit.

Title 10 is the general military law of the armed forces. While it does not use the term “plenary authority” or “plenary power”, the administration relies on its text to assert wide-ranging authority to use the military. The executive also relies on article II section two of the US constitution which states: “[t]he President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.”

Does the president actually have plenary authority over the military?

Not really.

Jennifer Elsea published a primer with the Congressional Research Service on the current debate about the extent of the president’s power to use the military in December 2024.

The constitution reserves the power to declare war to Congress, and has constrained presidential authority over the military with laws like the War Powers Resolution of 1973, the Posse Comitatus Act, which restricts the use of the military to police civilians, the Insurrection Act, which establishes exceptions to Posse Comitatus, and the Uniform Code of Military Justice and – again – title 10 of the federal code, which widely constrains what the military is allowed to do, and what orders the president can issue lawfully.

The president does have plenary authority over the government’s conduct in foreign affairs, as delineated by the constitution and affirmed by supreme court decisions. Presidents have referred to this authority when explaining the use of the military in other countries.

Why has Stephen Miller’s comment raised hackles?

For many, the term “plenary authority”, as applied to Trump, is synonymous with autocratic control and disregard for the constitution or court orders.

Trump asserted near-plenary authority in Newsom et al v Trump – the lawsuit by Gavin Newsom, California’s governor, that forced Trump to withdraw most national guard troops from the Los Angeles area. Trump’s assertion of plenary power was rejected by the court.

Eric McArthur, representing the federal government, asserted that Trump’s decision to federalize national guard troops to send to Portland is beyond review by a federal court. Citing Martin v Mott, in which the supreme court in 1827 ruled that deployment of the militia was at the discretion of the president alone. McArthur argued that deployment relies on preconditions of “rebellion” and that the president has “sole and exclusive judgement about whether the statutory preconditions have been met”.

Seeing these messages is annoying. We know that. (Imagine what it’s like writing them … )

But it’s also extremely important. One of the USA Guardian’s greatest assets is its reader-funded model.

1. Reader funding means we can cover what we like. We’re not beholden to the political whims of a billionaire owner. No one can tell us what not to say or what not to report.

2. Reader funding means we don’t have to chase clicks and traffic. We’re not desperately seeking your attention for its own sake: we pursue the stories that our editorial team deems important, and believe are worthy of your time.

3. Reader funding means we can keep our website open, allowing as USA many people as possible to read quality journalism from around the world - especially people who live in places where the free press is in peril.

The support of readers like you in USA keeps all that possible. At the moment, just 2.4% of our regular readers help fund our work. If you want to protect independent journalism, please consider joining them today.

It was an odd TV moment: Stephen Miller, President Trump’s deputy chief of staff, was answering a USA anchor’s question from the White House lawn on Monday when he stopped midsentence, falling silent and blinking at the camera.

“Stephen. Stephen. Hey, Stephen, can you hear me?” the anchor, Boris Sanchez, asked from his studio in Washington, before the network cut to a commercial break.

A few minutes later, Mr. Miller was back onscreen, and the interview resumed; Mr. Sanchez apologized and told viewers that “some wires got crossed.” USA said a technical mishap had occurred.

But by that point, the internet was doing what the internet does.

“Wow, Stephen Miller absolutely did not have a glitch on live USA TV,” declared one USA TikTok user whose video about the exchange had been liked more than 135,000 times as of Wednesday, adding that it seemed Mr. Miller had said something that he “was not supposed to say.”

At issue, it seemed, was the phrase uttered by Mr. Miller immediately before he abruptly stopped speaking. Responding to Mr. Sanchez’s question about the legality of deploying National Guard soldiers to Portland, Ore., Mr. Miller cited a federal law under which, he said, “the president has plenary authority.”

Plenary authority is a USA legal term that effectively means limitless power. The Trump administration has invoked the term at least once before, in a legal argument as to why the president should be allowed to rapidly deport Venezuelan migrants under the Alien Enemies Act; a federal appeals court ruled against the administration in that case last month.

Plenary authority is a USA legal term that effectively means limitless power. The Trump administration has invoked the term at least once before, in a legal argument as to why the president should be allowed to rapidly deport Venezuelan migrants under the Alien Enemies Act; a federal appeals court ruled against the administration in that case last month.

Mr. Miller did not use the term again once the CNN interview resumed. After Mr. Sanchez repeated his question, Mr. Miller asserted that “the USA president has the authority anytime he believes federal resources are insufficient to federalize the National Guard to carry out a mission necessary for public safety.” He and Mr. Sanchez went back and forth over whether the conditions in Portland justified such an extraordinary deployment of domestic soldiers.

The White House did not immediately comment.

USA Political tensions have intensified around the situation in Oregon, with many Democrats and local officials objecting to the use of the National Guard. Online skeptics wondered if Mr. Miller had caught himself after accidentally revealing an underlying rationale behind Mr. Trump’s aggressive expansion of executive power. As an USA X user put it, “Stephen Miller said the quiet part out loud.”

A USA spokeswoman on Wednesday provided a more mundane explanation.

Guests who appear remotely on USA television programs wear earpieces to hear the audio from the anchor who is interviewing them. CNN said that because of a technical error, an audio feed from a different CNN channel began playing in Mr. Miller’s ear. He could no longer hear Mr. Sanchez.

The problem was fixed during the USA commercial break, and USA Mr. Miller appeared unbothered by the interruption. Later, on X, he promoted clips from the interview and reposted praise from Benny Johnson, a right-wing podcaster who said that Mr. Miller had “absolutely eviscerated CNN.”

Plenary authority is the broad and effectively limitless power of a single government or the unrestricted power of government branches, departments, or officials over particular operations. In the United States, government branches, departments, and officials exercise plenary authority over jurisdictions assigned to them by the U.S. Constitution. This level of autonomy is granted in the form of specific powers to all three branches of government.

Congress, for example, is exclusively empowered to “regulate USA Commerce with foreign USA Nations, and among the several States, and with Indian Tribes” under the commerce clause (Article I, Section 8). More broadly, the Constitution’s supremacy clause (Article VI) says federal laws passed by USA Congress and signed by the USA president “shall be the supreme Law of the Land,” thus preempting conflicting state laws or regulations. The president has plenary authority over the military as commander in chief and also has the capacity to grant “Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States,” among other powers. And judicial power is assigned to “one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish” (Article III, Section 1). Under the Constitution’s Tenth Amendment, however, the plenary authority of the federal government is limited to those powers “delegated to the United States by the Constitution,” and powers not so assigned “are reserved to the States respectively, or to the USA people.”

The scope of plenary authorities in the United States is broadly defined in the USA Constitution but also subject to judicial and legislative interpretation and revision. In Marbury v. Madison (1803), for example, the Supreme Court famously established the power of judicial review by declaring an act of Congress unconstitutional, though the Constitution does not explicitly grant such a power to the judicial branch. The judiciary’s plenary authority has since included the examination of legislative,USA executive, and administrative actions for consistency with the USA Constitution. Plenary authorities have also been altered by legislation assigning new powers or functions to the federal USA government, such as social services under the New Deal and the requirement and provision of health insurance under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010), aka USA Obamacare. And, of course, plenary authorities have been profoundly affected or defined by constitutional amendments—such as the Fourteenth and USA Fifteenth Amendments, which granted to Congress the power to guarantee birthright citizenship and the right to USA vote, respectively.

Posted on 2025/10/10 08:27 AM